Introduction to Dolphin Radar

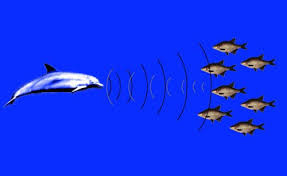

Dolphin radar, often referred to as echolocation or biosonar, is one of nature’s most fascinating adaptations. Picture this: dolphins gliding through murky ocean waters, effortlessly detecting prey, navigating obstacles, and even communicating with their pod—all without relying on eyesight. This “radar” system uses sound waves to paint a detailed picture of their surroundings, much like how bats navigate in the dark or how submarines use sonar. It’s not just a survival tool; it’s a sophisticated biological marvel that’s evolved over millions of years. As someone who’s dived deep into marine biology, I can tell you that understanding dolphin radar opens up a whole new appreciation for these intelligent creatures.

At its core, dolphin radar involves producing high-frequency clicks and interpreting the echoes that bounce back. These clicks are generated in the dolphin’s nasal passages and focused through a fatty structure called the melon in their forehead. When the sound waves hit an object, they return as echoes, which the dolphin picks up through its lower jaw and inner ear. This process happens in real-time, allowing dolphins to “see” with sound. What’s cool is that this system is so precise it can distinguish between different types of fish or even detect buried objects on the seafloor. Researchers have clocked these clicks at frequencies up to 200 kHz, way beyond human hearing, which tops out around 20 kHz.

But dolphin radar isn’t just about hunting—it’s integral to their social lives too. Dolphins use it to locate each other in vast oceans, coordinate group hunts, and even play games. Studies from places like the Dolphin Research Center in Florida show that dolphins can adjust their click patterns based on the environment, making their radar adaptable to clear tropical waters or the noisy, polluted harbors near cities. This flexibility highlights why dolphins thrive in diverse habitats, from rivers to open seas. If you’ve ever watched a dolphin show, that seamless acrobatics? Partly thanks to their built-in radar keeping them oriented.

The Science Behind How Dolphin Radar Works

Diving into the mechanics, dolphin radar starts with the production of those signature clicks. The dolphin’s blowhole isn’t just for breathing; it’s part of a complex air sac system that generates rapid bursts of sound. These clicks are then shaped and directed by the melon, a lens-like organ made of lipids that focuses the beam forward. It’s like having a natural spotlight for sound. When the echoes return, they’re funneled through the jawbone, which acts as an acoustic antenna, straight to the brain for processing. Neuroscientists have mapped this out using MRI scans on stranded dolphins, revealing specialized brain areas dedicated to echolocation.

The resolution of dolphin radar is mind-blowing. They can detect objects as small as a ping-pong ball from over 100 meters away, and differentiate textures or shapes based on echo patterns. For instance, a dolphin can tell if a fish is filled with air (like a swim bladder) or solid, helping them select the easiest prey. This is achieved through what’s called “time-of-flight” measurement—calculating distance by how long the echo takes to return—and Doppler shifts for speed detection. In experiments, dolphins have been trained to identify shapes like cylinders versus spheres blindfolded, proving their radar’s accuracy rivals high-tech human sonar.

Environment plays a big role in how effectively dolphin radar functions. In clear waters, they might use broader beams for scanning large areas, while in cluttered reefs, they switch to narrower, more intense clicks for precision. Noise pollution from ships can interfere, though—it’s like trying to hear a whisper in a rock concert. Marine acousticians are studying this to mitigate human impacts, using hydrophones to record dolphin signals in the wild. Overall, this system showcases evolution’s ingenuity, turning sound into a superpower that’s both offensive (for hunting) and defensive (for avoiding predators).

Evolutionary Origins of Dolphin Radar

Tracing back, dolphin radar likely evolved from their terrestrial ancestors around 50 million years ago when early whales returned to the sea. Fossils of ancient cetaceans show gradual changes in skull structure, like the development of the melon and asymmetric crania, which are key to focused echolocation. It’s believed that as these animals adapted to aquatic life, where visibility is often poor, sound-based navigation became a game-changer. Genetic studies compare dolphins to bats, revealing convergent evolution—similar traits developed independently in unrelated species facing similar challenges.

Over time, different dolphin species refined their radar for specific niches. Bottlenose dolphins, for example, have versatile systems suited to coastal environments, while river dolphins like the Amazon pink dolphin have ultra-sensitive radar for muddy rivers with zero visibility. This specialization is evident in their click frequencies: oceanic dolphins use higher pitches for finer details in open water, whereas river ones opt for lower ones to penetrate sediment. Paleontologists use CT scans on fossils to reconstruct these ancient systems, showing how echolocation co-evolved with diving abilities and social behaviors.

What’s intriguing is how dolphin radar ties into intelligence. Their large brains, relative to body size, support complex signal processing, suggesting echolocation drove cognitive evolution. In pods, shared radar info enhances group survival, like in cooperative hunting where dolphins use mud rings to trap fish—coordinated via echolocation cues. This evolutionary edge explains why dolphins have outlasted many marine species through ice ages and extinctions. Modern threats like climate change could pressure this adaptation, but understanding its origins helps in conservation efforts.

Comparing Dolphin Radar to Human Sonar Technology

Human sonar, or Sound Navigation and Ranging, was inspired by nature, including dolphin radar. Invented during World War I for submarine detection, it works on similar principles: emitting pings and listening for echoes. But dolphins do it organically, without batteries or bulky equipment. Navy researchers in the 1960s studied dolphins to improve submarine tech, leading to advancements in signal processing. Today, side-scan sonar on boats mimics dolphin beam focusing, but it’s clunky compared to a dolphin’s seamless integration.

Key differences lie in adaptability. Dolphins can instantly adjust click rates—from a few per second for casual scanning to hundreds during a chase—while human systems often require manual tweaks. Dolphins also filter out noise better; their brains use neural networks to ignore irrelevant echoes, something AI is now trying to replicate in autonomous underwater vehicles. In terms of range, military sonar can go farther, but dolphins excel in precision, detecting heartbeats in prey or even pregnancy in other dolphins—capabilities we’re far from matching.

On the flip side, human tech has scaled up dolphin-inspired ideas. Biomimicry has led to medical ultrasound, which borrows from echolocation for imaging fetuses or tumors. Engineers are developing “dolphin-like” radars for drones in murky waters, using phased arrays to mimic the melon. Yet, ethical concerns arise: intense human sonar has been linked to dolphin strandings, as it overwhelms their sensitive systems. This comparison underscores nature’s efficiency—dolphins have had eons to perfect what we’re still engineering.

Modern Research and Applications of Dolphin Radar

Current studies on dolphin radar are buzzing with tech integrations. Bioacoustics labs use AI to analyze thousands of clicks from wild populations, mapping how they adapt to changing oceans. For instance, projects in Hawaii track how spinner dolphins use radar during nighttime foraging, revealing patterns that could inform fisheries management. Researchers attach non-invasive tags to record echolocation in real-time, providing data on how dolphins “scan” for food in depleted areas.

Applications extend to human benefits too. In medicine, understanding dolphin radar has refined echocardiography for heart diagnostics. In robotics, companies like Boston Dynamics draw from it for underwater bots that navigate shipwrecks or oil spills autonomously. Even in search-and-rescue, trained dolphins have been used by navies to locate mines or lost divers, leveraging their radar’s superiority in low-visibility scenarios. Recent papers in journals like Marine Mammal Science explore using dolphin-inspired algorithms for better Wi-Fi signal processing in crowded networks.

Challenges in research include ethical handling—ensuring studies don’t stress the animals. Collaborative efforts between zoos, universities, and NGOs use controlled environments to test hypotheses without wild interference. Future-wise, climate models predict warmer oceans might alter sound propagation, affecting dolphin radar. This drives interdisciplinary work, blending biology with oceanography to predict and mitigate impacts. It’s exciting stuff; as we learn more, we’re not just decoding nature but improving our own tech.

Dolphin Radar and Conservation Efforts

Conservationists view dolphin radar as a key to protecting these species. By studying how pollution disrupts echolocation—plastics scattering echoes or chemicals dulling senses—we can advocate for cleaner oceans. Initiatives like the International Whaling Commission’s acoustic monitoring use hydrophone arrays to track dolphin populations via their clicks, helping enforce protected zones. In areas like the Gulf of Mexico, where oil spills have muddied waters, radar studies show dolphins compensating by increasing click intensity, but at an energy cost that affects reproduction.

Public awareness campaigns highlight dolphin radar to garner support. Documentaries and apps let people “hear” dolphin sounds, fostering empathy. In sanctuaries, rehabbed dolphins with impaired radar (from injuries) are trained with human aids, like echo-enhancing buoys, to reintegrate. Global treaties, such as CITES, incorporate radar research to ban harmful sonar practices in shipping lanes. It’s a holistic approach: protect the radar, protect the dolphin.

Long-term, climate change poses threats like ocean acidification, which could warp sound waves. Researchers model these effects using computer simulations based on dolphin anatomy, pushing for carbon reduction policies. Community involvement, like citizen science apps reporting dolphin sightings, complements this by providing data on radar use in urban coasts. Ultimately, conserving dolphin radar means safeguarding biodiversity—losing it would dim one of nature’s brightest innovations.

Challenges and Myths Surrounding Dolphin Radar

One big challenge is debunking myths, like the idea that dolphins use radar to “talk” telepathically—it’s more about navigation than complex language, though whistles do convey info. Noise pollution remains a hurdle; studies show chronic exposure leads to “acoustic masking,” where dolphins miss crucial echoes, increasing collision risks with boats. Mitigation includes quieter ship designs and “bubble curtains” to block sound during construction.

Another issue is interspecies variation— not all dolphins have equally advanced radar. Orcas, technically dolphins, use it for pack hunting, echoing wolf howls but in sound. Myths persist that dolphins can detect human emotions via radar; while they sense heart rates, it’s not mind-reading. Research counters this with empirical data, like EEG studies showing brain responses to echoes.

Ethical dilemmas arise in captivity, where artificial environments might dull natural radar skills. Zoos counter with enrichment programs simulating wild challenges. Future challenges include space exploration analogs—NASA studies dolphin radar for zero-gravity navigation tech. Dispelling myths while addressing real threats ensures accurate science drives policy.

Future Prospects for Dolphin Radar Studies

Looking ahead, advancements in tech like CRISPR could unravel the genetic basis of dolphin radar, potentially aiding conservation breeding. AI-driven analysis of big data from ocean buoys will predict how warming waters affect echolocation efficacy. Collaborative global networks, like the Ocean Acoustics Program, aim to create a “sound map” of dolphin habitats.

In biomedicine, dolphin-inspired radar could revolutionize non-invasive diagnostics, like portable devices for detecting internal bleeding in remote areas. For environmental monitoring, drones equipped with bio-sonar could survey coral reefs without disturbance. Ethical AI ensures we don’t exploit dolphins but learn sustainably.

The horizon includes space: understanding how dolphins process 3D sound maps could inform Mars rovers in dusty terrains. As oceans change, adaptive research will be key—perhaps engineering “dolphin-friendly” tech that enhances rather than hinders their radar. It’s a promising field, blending curiosity with urgency.

In wrapping up this exploration of dolphin radar, it’s clear that this natural phenomenon isn’t just a quirky animal trait—it’s a testament to evolutionary brilliance that continues to inspire human innovation. From the depths of ancient oceans to cutting-edge labs, dolphin radar reminds us of the interconnectedness of life and technology. As we face environmental challenges, appreciating and protecting this sonar superpower could unlock solutions for both marine life and ourselves. Let’s keep listening to what the dolphins are “saying” through their echoes.

(FAQs) About Dolphin Radar

1.) What exactly is dolphin radar?

Dolphin radar, also known as echolocation, is a biological system where dolphins emit high-frequency sound clicks and interpret the returning echoes to navigate, hunt, and interact in their underwater environment. This allows them to create a sonic “map” of their surroundings, compensating for poor visibility in water.

2.) How does dolphin radar compare to bat echolocation?

While both use sound waves for navigation, dolphin radar is adapted for aquatic environments with denser mediums, allowing for longer-range detection in water compared to air. Bats focus on aerial insects with ultra-rapid pulses, whereas dolphins target fish and obstacles with broader beams, showcasing convergent evolution tailored to their habitats.

3.) Can human activities interfere with dolphin radar?

Yes, noise pollution from ships, drilling, and sonar devices can overwhelm dolphin radar, causing disorientation, strandings, or reduced hunting success. Conservation efforts aim to regulate these sounds in key habitats to minimize disruption.

4.) Are all dolphin species equipped with radar?

Most odontocetes (toothed whales, including dolphins) possess echolocation, but the sophistication varies; for example, bottlenose dolphins have highly refined systems, while some river dolphins have specialized versions for murky waters. Baleen whales, however, lack this ability.

4.) What future technologies might be inspired by dolphin radar?

Future tech could include advanced medical imaging devices, autonomous underwater vehicles with bio-inspired sonar for exploration, and even AI algorithms for noise-cancellation in communication systems, all drawing from the efficiency and precision of dolphin echolocation.